Notes: Ministry of Finance forecasts represented by larger dots. The other forecasts included are by the Bank of Finland, the European Commission, the IMF, the OECD, Labore, Etla and PTT.

The Economic Policy Council was established in January 2014 to provide independent evaluation of economic policy in Finland. According to the government decree (61/2014), the Council is tasked with evaluating:

The Council is appointed by the government based on a proposal by economics departments of Finnish universities and the Academy of Finland. Council members are appointed for four-year terms and participate in the Council’s work alongside their regular duties.

In our previous report, we assessed the fiscal consolidation package outlined in Prime Minister Petteri Orpo’s government programme, with a particular focus on measures to increase labour supply. In this report, we provide an overview of the implementation of the government’s overall consolidation package and examine the supplementary measures introduced in 2024 as part of our evaluation of the government’s fiscal policy. We also address the financial situation of the wellbeing services counties and discuss certain structural issues related to regional labour markets in Finland.

The Council relies primarily on forecasts from the Ministry of Finance and does not produce its own macroeconomic or fiscal projections. The latest forecast utilised in this report is the Ministry of Finance’s Winter 2024 Economic Survey.

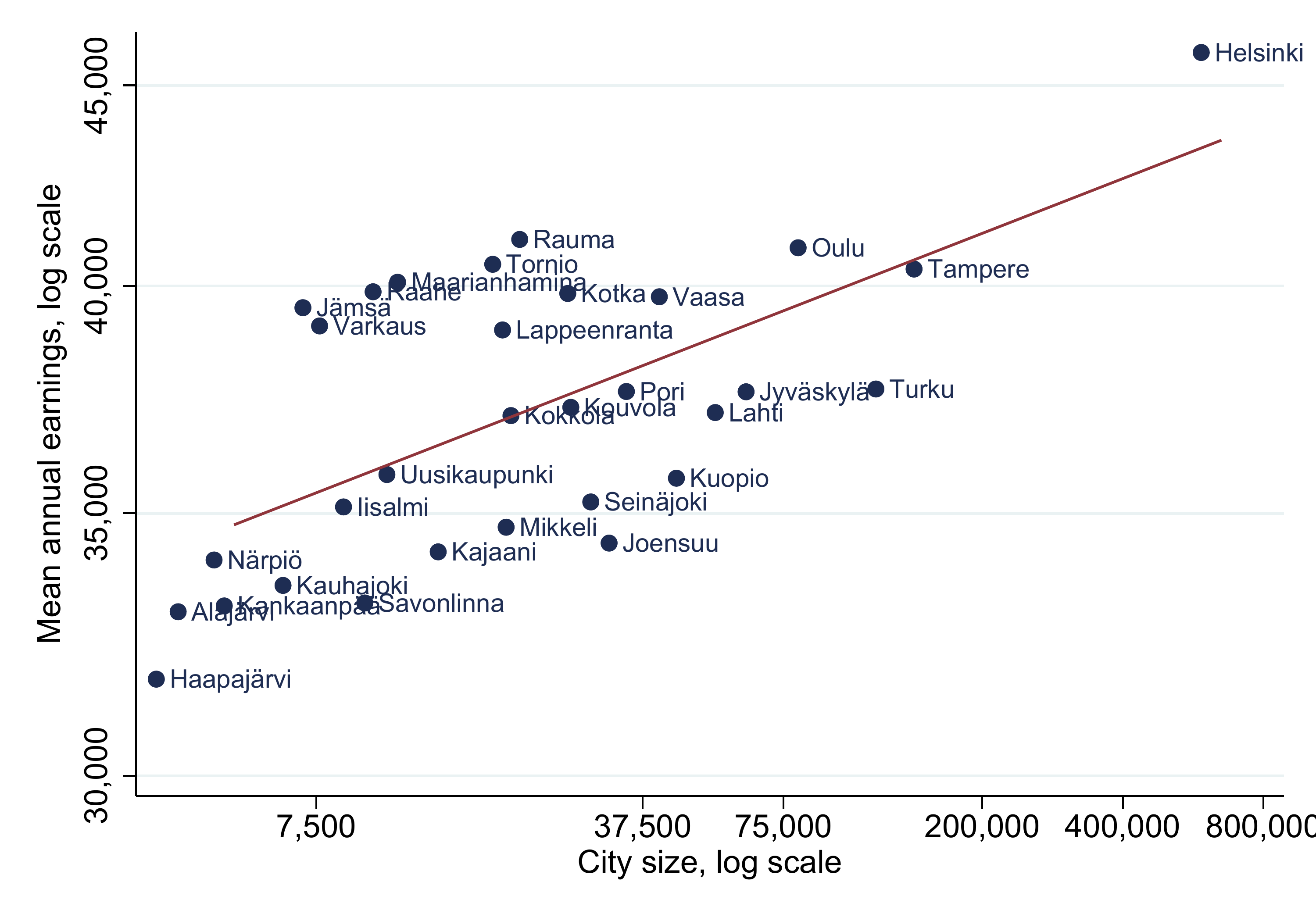

The Council can commission research to support its work. These commissioned studies reflect the views of their authors, which may or may not coincide with those of the Council. Two background reports have been published in connection with this Council report. Cristina Bratu and Teemu Lyytikäinen analysed the urban wage premium in Finland. Veikko Uusitalo, Merja Kauhanen, Annika Nivala and Tuomo Suhonen studied the geographical and occupational mismatch in Finland. We discuss these studies in the last chapter of this report.

The Council organised a seminar on the finances of the wellbeing services counties in November 2024. We thank all the participants in the seminar, and we wish to especially thank Tanja Rantanen, Ilkka Luoma and Tuulia Hakola-Uusitalo for sharing their views on the topic.

The Council expresses its gratitude to the many experts who have shared their insights. We are particularly thankful to Lassi Ahlvik, Ilari Ahola, Marketta Henriksson, Janne Huovari, Jukka Hytönen, Aleksi Kalenius, Jenni Kellokumpu, Peetu Keskinen, Harri Kähkönen, Jussi Lammassaari, Juri Matinheikki, Seppo Orjasniemi, Marja Paavonen, Niina Suutarinen, Roope Uusitalo and Antti Väisänen for valuable discussions and for patiently responding to many detailed questions.

We are also thankful to Anna-Maija Juuso, Tero Järvelä, Mia Klinga, Riikka Könönen, Anne Moilanen, Anita Niskanen, Marjo Nygren, Ida Pöyhönen, Sanna Tiensuu, Sari Virtanen and Outi Örn of VATT for their help in administration and communications.

Helsinki, 28 January 2025

Niku Määttänen, Chair

Seija Ilmakunnas, Vice-Chair

Hilde Bjørnland

Liisa Häikiö

Tuukka Saarimaa

Anni Huhtala, Secretary General, until July 31, 2024

Jenni Jaakkola, Secretary General, since September 1, 2024

Henri Keränen, Researcher

Finland is experiencing a more severe economic downturn than the Nordics and the broader euro area, influenced by factors such as trade sanctions related to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and subsequent disruptions in foreign trade. However, positive growth observed in more recent quarters may indicate the beginning of a stabilisation phase.

Following recent policy rate cuts by the European Central Bank, short-term nominal interest rates in Finland have begun to decline. These lower rates, particularly relevant for most mortgage borrowers, are expected to boost aggregate demand in 2025. In contrast, long-term real interest rates, which are critical for assessing the long-term fiscal cost of public debt, have remained relatively stable following their sharp increase from 2022 to 2023.

Finland has also experienced the largest employment rate decline among its Nordic peers since early 2023. The Ministry of Finance forecasts a slight decrease in the employment rate in the near term, followed by a modest increase as government measures to boost employment gradually take effect.

The first two years of operation were financially challenging for the wellbeing services counties. Their expenditures rose rapidly compared to municipal spending on the same services in 2022, and many counties ran significant deficits.

The spending increases are largely due to factors unrelated to the health and social services reform, such as surging inflation in 2022–2023 and higher wages. Moreover, the counties have had little time to implement productivity-enhancing reforms. For these reasons, the rapid growth in spending and deficits in 2023–2024 should not be seen as evidence of the reform’s failure.

Still, questions remain about whether the current funding model functions optimally. Counties that incurred deficits in their first two years are required to offset these with corresponding surpluses by the end of 2026. This requirement means that many counties should try to reduce their spending significantly in 2025 and 2026. However, if they achieve this, they may find themselves in a position to substantially increase spending in 2027 compared to the preceding years. To safeguard key services, it would be preferable to allow counties to spread expenditure adjustments over a longer period.

The government should consider providing this additional flexibility temporarily. This need not entail an increase in long-term central government funding.

A major challenge for counties is the difficulty and high cost of recruiting qualified staff. The severe scarcity of doctors may be the single most significant obstacle to ensuring adequate healthcare services. The government’s decision to increase reimbursements for the use of private medical services may not alleviate the problem, as it is likely to increase the demand for doctors in the private sector.

Addressing this challenge requires reallocating doctors’ time to tasks where their expertise is most critical. Increasing the supply of doctors is also essential. One option is for counties to fund medical training for students at foreign universities, on the condition that they either work for the counties after graduation or repay their training costs. The government should also review language requirements to attract more migrant doctors. Finland’s growing immigrant population would benefit from access to a wider range of languages, and many Finns could likely communicate effectively with a doctor who does not have perfect command of Finnish or Swedish.

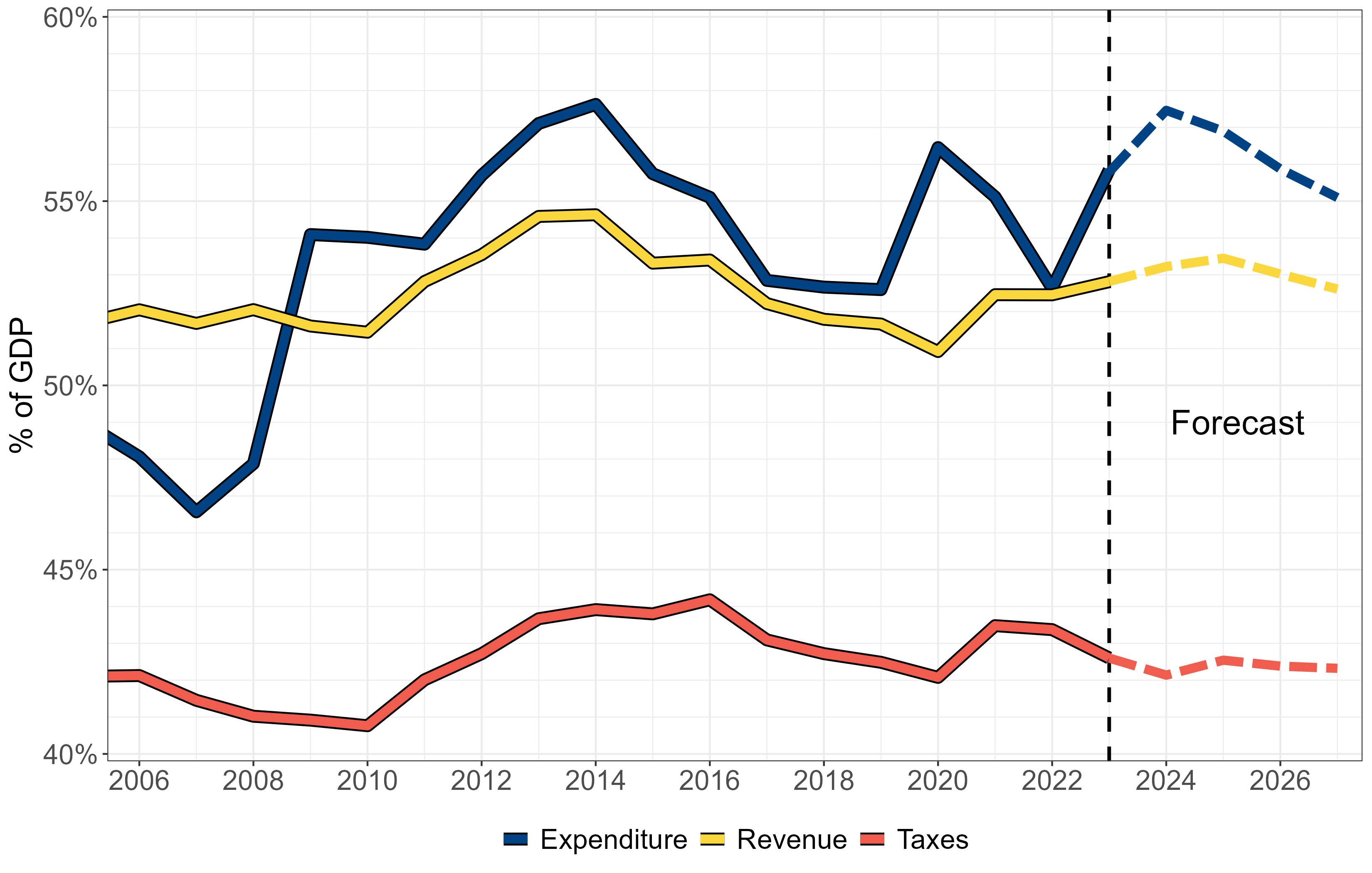

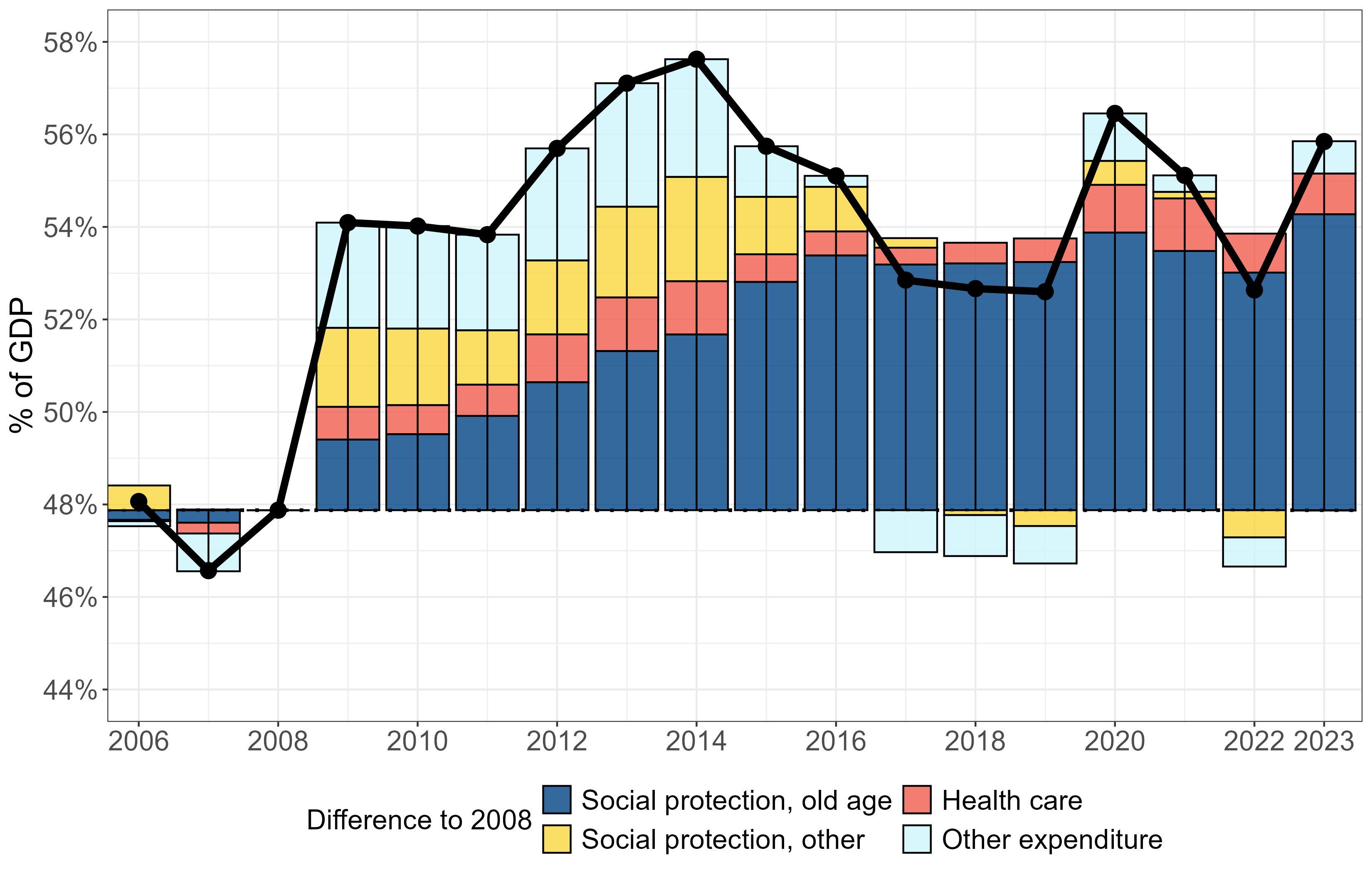

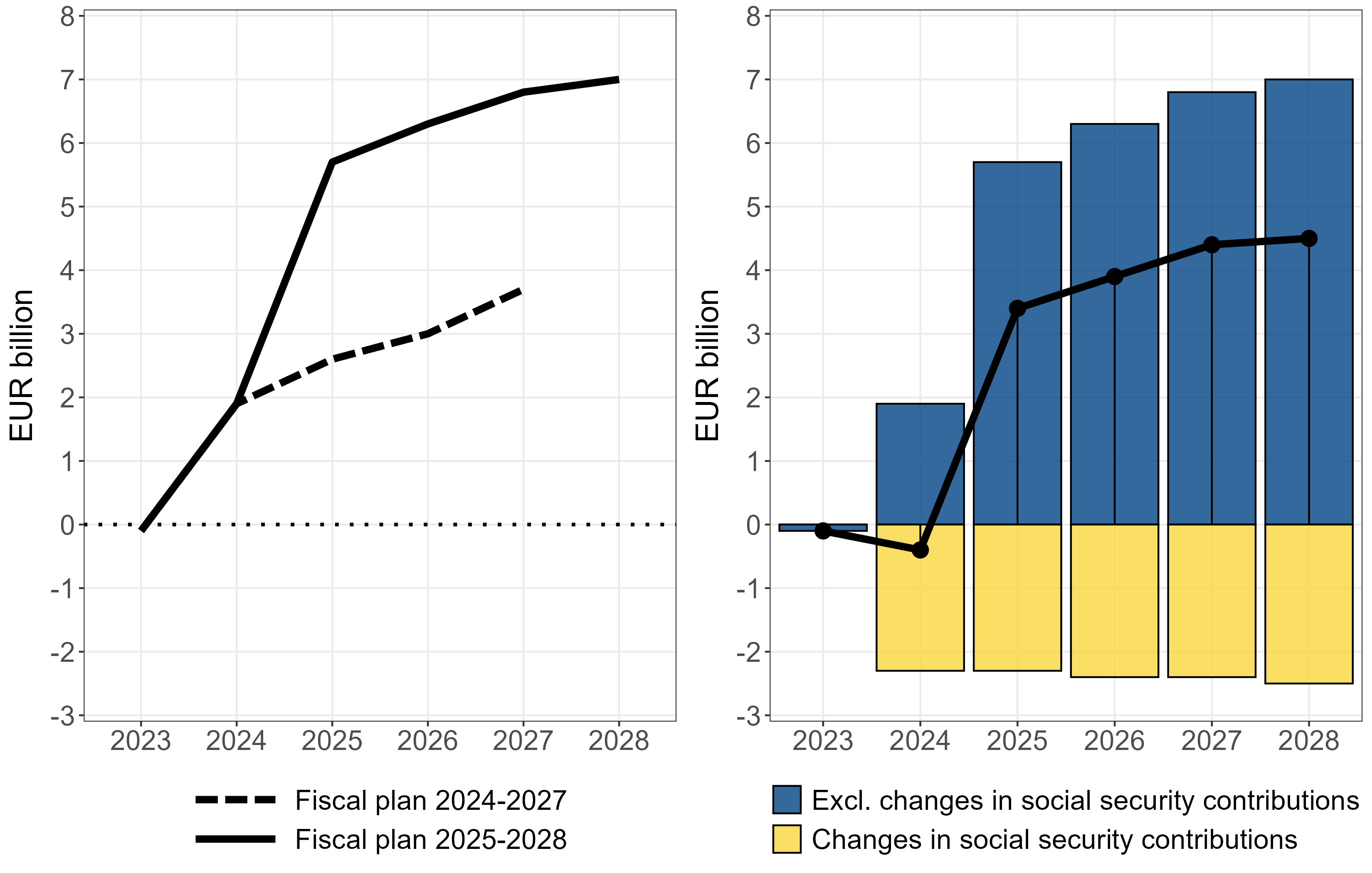

The government has implemented most of the direct savings measures outlined in its programme, including cuts to social benefits and reductions in certain social and health services, either in 2024 or from the beginning of 2025. In addition, it has introduced significant new fiscal measures, such as a 1.5 percentage point increase in the standard VAT rate, a slight tightening of pension income taxation, and further savings in public administration and social and health services. While the VAT increase took effect in September 2024, most other measures will be implemented in 2025. These new measures significantly enhance the credibility of the government’s fiscal policy by underscoring its commitment to strengthening public finances.

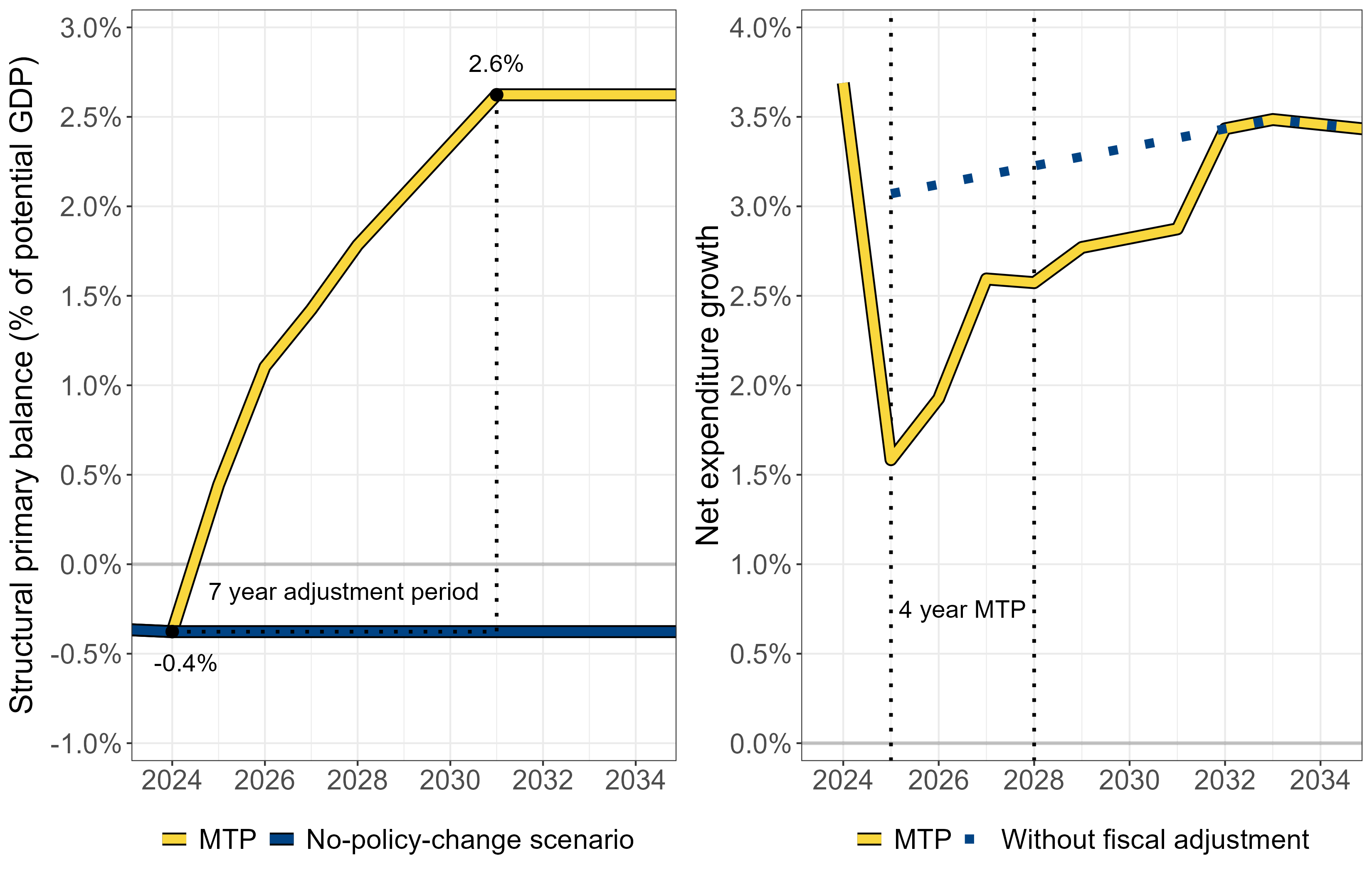

Despite the implementation of the government programme and new consolidation measures, the public debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to grow relatively quickly in 2025. Furthermore, it remains uncertain whether the measures taken so far will suffice to achieve the government’s primary fiscal objective of stabilising the debt ratio by the end of its term. One contributing factor is the weakening of the business cycle since the start of the government’s term.

Another reason is that some consolidation measures were uncertain from the outset. For example, the government programme assumed that labour supply measures would strengthen public finances by approximately EUR 2 billion annually through higher employment. These measures aim to improve labour supply incentives by reducing transfers for those not working. However, their impact is difficult to estimate and will in any case take time to fully materialise. The weakened economic situation is likely to have further delayed their employment effects. A third reason is the rapid growth in spending by the wellbeing services counties.

The government’s consolidation measures significantly tighten fiscal policy in 2025 compared to 2024. The recent rise in unemployment and Finland’s lower inflation compared to the rest of the euro area suggest that the timing of these measures is not ideal from the perspective of stabilising aggregate demand. On the other hand, employment remains relatively high compared to pre-COVID-19 levels, the output gap is expected to improve in 2025, and public spending continues to rise even without new policy decisions due to population ageing. Additionally, as mentioned above, the recent easing of euro area monetary policy should begin to support aggregate demand in 2025. Given these conditions and the risks of a rising debt ratio, the government’s fiscal stance in 2025 does not appear overly restrictive. However, unless the business cycle improves rapidly, it would be prudent to avoid further measures that substantially reduce aggregate demand in the very short term.

Regardless of the economic cycle, the government should pursue reforms to strengthen public finances in the long run. The pension reform mentioned in the government programme represents a key opportunity in this regard.

Stronger measures are also needed in climate policy to reduce emissions in the effort-sharing sector and enhance carbon sinks in the land-use sector. Missing these targets undermines Finland’s climate credibility and heightens the fiscal risks. From a public finance perspective, greater reliance on taxes and fees related to emissions or carbon sink reductions, rather than subsidies and grants, would be preferable.

Due to agglomeration effects, labour productivity can probably be improved by increasing the size of the largest cities. Cities can only grow in population if they increase the supply of housing and commercial real estate. This underlines the importance of policies aimed at increasing the supply of housing in cities with the highest housing costs. Continuing the government’s cooperation with municipalities through land use, housing and transport (MAL) agreements is likely to be essential in this regard.

However, the concentration of population in cities can have negative effects on other parts of Finland. Labour migration from abroad can support productivity growth by facilitating the expansion of labour markets around the largest cities, without necessarily causing population decline elsewhere.

The Finnish labour market seems to have become less efficient in matching unemployed jobseekers with vacancies in recent decades. This trend does not seem to be due to an increase in regional or occupational mismatches between jobseekers and vacancies. Regional mismatch refers to the geographical distance between jobseekers and vacancies, while occupational mismatch refers to a mismatch between jobseekers’ skills and the requirements of available jobs. Urbanisation has likely improved employment by allowing unemployed jobseekers to find vacancies matching their skills and education more quickly.

Public employment services have been transferred from central government to the municipalities. While this decentralisation alone is unlikely to have a strong direct impact on employment, the reform includes changes in incentives that could strengthen employment outcomes. For example, municipalities now bear an increasing share of the costs of unemployment benefits paid to their residents, and these costs increase with the duration of unemployment. This should motivate municipalities to adopt more effective policies to improve employment in the local labour market.

However, there are risks associated with the reform. Removing barriers to employment often requires close cooperation between employment and health service providers. Under the new system, the municipalities are responsible for employment services, while the wellbeing services counties are responsible for health services. This division of responsibilities may lead to cost-shifting that harms those most in need of measures to support their ability to work. It will be important to monitor how municipalities and wellbeing counties address these challenges.

Since the Council’s previous report, Finland’s economic outlook has worsened. Figure 2.1.1, which plots GDP growth forecasts for Finland made since September 2023, shows how the growth forecasts for 2024 have been revised downwards since then. For instance, in the forecast made in autumn 2023, the Ministry of Finance forecast growth of for 2024, while the most recent forecast in December 2024 puts growth for 2024 at . Similarly, other forecasting institutions have revised their GDP forecasts downwards as more recent economic data has shown that the economic growth projected for 2024 has not materialised. The only forecast in 2023 to predict negative growth for 2024 was published by the Bank of Finland in December 2023.

Notes: Ministry of Finance forecasts represented by larger dots. The other forecasts included are by the Bank of Finland, the European Commission, the IMF, the OECD, Labore, Etla and PTT.

Even though the annual growth rate in 2024 is forecast to be negative, a look at quarterly GDP reveals that by the end of 2024 aggregate output started to grow (Figure 2.1.2). Figure 2.1.1 also shows that there have been no systematic downward revisions to growth forecasts for 2025. The most recent Ministry of Finance (2024b) forecast puts growth at . Among the forecasting institutions included in Figure 2.1.1, Bank of Finland (2024) forecast published in December 2024 had the lowest GDP growth forecast for 2025 at .

Figure 2.1.2, which tracks quarterly real GDP developments in selected countries since the last quarter of 2019, shows that Finland’s output growth continues to lag behind both its Nordic peers and the euro area average. Growth in Finland turned negative in 2022 following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It is plausible that the Finnish economy has suffered the most from the effects of the conflict, including trade sanctions against Russia, among this group of countries. Growth in Sweden and the euro area has also stagnated, which further negatively impacts the Finnish economy through foreign trade. In contrast, growth in the US and Denmark has been relatively strong, with Denmark benefiting from the recent success of the pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk.

Sources: Eurostat and FRED.

Figure 2.1.3 decomposes the annual growth in Finnish GDP into its main expenditure components. Private investment is typically a highly pro-cyclical component of GDP, rising in upturns and falling in downturns. The figure shows that this has also been the case in the most recent downturn: private investments fell sharply in 2023 (by about ), contributing negatively to aggregate growth (with a growth contribution of about as private investments are around a fifth of total GDP). The construction sector, in particular, experienced a severe contraction in 2023 and in 2024. This decline largely explains the overall fall in investment expenditure as construction constitutes a large share of total investment in the Finnish economy. According to the Ministry of Finance (2024b) forecast, private investments continued to decline in 2024 but are expected to return to growth in 2025.

Sources: Statistics Finland, Ministry of Finance (2024b) and Council’s calculations. Notes: The category Other consists of all other components contributing to GDP: changes in inventories, net acquisitions of valuables and statistical discrepancy.

In a small open economy like Finland, changes in net exports can also make a large contribution to aggregate output. In 2023, net exports made a large positive contribution to GDP, while aggregate growth was negative. However, this positive contribution was almost entirely due to a fall in imports, as export growth was close to zero in 2023. According to the Ministry of Finance (2024b) forecast, net exports are expected to have a small positive contribution to GDP in 2024, with imports still falling slightly and with growth in exports being small but positive. In 2025 both exports and imports are forecast to grow, but import growth is projected to be higher than export growth, meaning that in total the contribution of net exports to GDP growth is forecast to be slightly negative.

Figure 2.1.3 shows that growth in 2025-2027 is forecast to come mainly from increases in private consumption and private investment. In 2025, general government is also forecast to make a positive contribution, although the growth will come mainly from public investment, as the volume of government consumption is forecast to decline slightly in 2025 (Ministry of Finance, 2024b). The increase in public investment largely reflects deliveries of new military equipment (see chapter 4 on fiscal policy).

A typical measure of the cyclical position of the economy is the output gap: the difference between actual and potential GDP. Figure 2.1.4 plots the output gap for Finland and the euro area based on estimates by the European Commission. According to the Commission’s Autumn 2024 forecast, Finland’s output gap is around , compared to approximately for the euro area. This suggests that Finland is experiencing a more significant cyclical downturn than the euro area economy on average. However, Finland’s output gap is also forecast to shrink rather quickly in 2025 and 2026. At the same time, it is important to note that real-time estimates of the output gap are known to be prone to large ex-post revisions (see e.g. Rybarczyk, 2023).

Source: European Commission (AMECO database).

Inflation continued to decline in 2024 from the elevated levels observed in 2022 and early 2023, as shown in Figure 2.2.1. Annual HICP (Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices) inflation was on average roughly in 2024. Service inflation has been the main contributor to annual inflation, while the decline in energy prices has had a negative contribution. Inflation in Finland has recently been lower than in the euro area, where according to Eurostat data the average for 2024 was around .

The most recent data indicates a slight uptick in inflation compared to previous months. This increase is partly attributable to the VAT hike implemented in September 2024, as well as a correction to the HICP index following an error in the price index of electricity, which affected annual inflation figures between August 2023 and July 2024. The Ministry of Finance (2024b) forecasts HICP inflation to be in 2025.

Source: Statistics Finland.

Falling inflation has allowed central banks to lower their policy rates. The ECB began reducing its key policy rates in June 2024, cutting the overnight deposit rate from to by December 2024. Euribor rates, to which the majority of Finnish mortgages are tied, have also declined throughout 2024. The decrease in Euribor rates also reflects expectations of further cuts in the ECB’s policy rates in the near future.

A decline in short-term nominal interest rates, coupled with relatively stable inflation, is likely to result in a lower real interest rate, the rate of interest net of inflation, in 2025 compared to 2024. This can be expected to boost aggregate demand in 2025, particularly compared to the situation in early 2024.

In our previous report (EPC, 2024), we noted that long-term real interest rates, based on the yields of inflation-indexed government bonds, have risen significantly in recent years. These rates are particularly relevant for assessing fiscal sustainability and the long-term cost of public debt. For instance, relatively high nominal interest rates on public debt may not pose a major concern if nominal tax revenues rise rapidly due to high inflation. By contrast, higher long-term real interest rates increase the (expected) long-term cost of public debt, requiring larger budget surpluses net of interest payments to stabilise the debt-to-GDP ratio.

Source: FRED.

Sources: Bank of Finland (Reuters), Agence France Trésor (Bloomberg). Notes: Maturity date in parentheses. French real yield is for OAT€i, which is indexed to euro area HICP.

Figures 2.2.2 and 2.2.3 show that real interest rates have remained relatively stable in 2024. Figure 2.2.2 plots a time series of the interest rate on 10-year inflation-indexed US government bonds, which rose sharply from 2022 to 2023 but hovered around throughout 2024. Similarly, the yield on the inflation-indexed French government bond, shown in Figure 2.2.3 (red line), increased in 2022 but remained largely unchanged in 2024 compared to 2023. The market yield on the French bond serves as a good proxy for Finland’s real interest rate environment, as the nominal yields of Finnish bonds (blue dots) and French bonds (yellow line) of similar maturities have tracked each other closely, as seen in Figure 2.2.3.

The Finnish labour market has certainly cooled from recent years: unemployment has risen while employment and open vacancies have gone down. Based on Statistics Finland’s monthly labour force survey data, the number of employed persons fell by an average of 18,000 and the number of unemployed persons rose by 33,000 between December 2023 and November 2024 compared with the same period the previous year (Table 2.3.1). The Ministry of Finance (2024b) forecasts that weak labour market conditions will persist in 2025: the unemployment rate is forecast to be in 2025 compared to in 2024.

In an international comparison among the group of countries in Figure 2.3.1, Finland’s employment rate has experienced the largest decline since the beginning of 2023. The employment rate of 20-64 year olds has dropped from in the first quarter of 2023 to in the third quarter of 2024. The gap in employment rates between Finland and the other Nordic countries has widened recently, although employment rates have also declined in Sweden and Norway. Still, when compared to its historical trends, Finland’s employment rate remained relatively high in 2024, as the annual employment rate for 20–64 year olds has only been higher in 2022 and 2023.

Looking ahead, the Ministry of Finance forecasts that the employment rate will decrease slightly to 76.3% in 2025, before rising to 76.8% in 2026, c.f. Ministry of Finance (2024b). The forecast assumes that the government’s measures to boost employment will gradually start to take effect but other factors such as the weak economic cycle mean that employment growth in the latest forecast is weaker than, for example, in the previous Ministry of Finance (2024a) forecast.

Source: Eurostat.

Figure 2.3.2 plots the Beveridge curve for Finland, following the analysis of Gäddnäs and Keränen (2023). The Beveridge curve describes the relationship between vacancies and unemployment: a higher vacancy rate is typically associated with a lower unemployment rate and vice versa. The figure shows a marked decline in vacancies and, as can be seen in the figure, vacancy and unemployment rates have recently moved more or less along the blue Beveridge curve, which represents the historical relationship between these two variables in recent Finnish data.

Source: Gäddnäs and Keränen (2023), updated with more recent data from Eurostat. Notes: The coloured Beveridge curves represent average positions of the curve in 1978-1990 (green curve), 1994-2012 (yellow curve) and 2013- (blue curve).

The cooling of the labour market has therefore materialised as a downward movement along the curve, characterised by fewer vacancies and higher unemployment. During the period from 2024Q1 to 2024Q3, there were fewer than open vacancies per unemployed person, compared to a ratio of approximately in 2022. In other words, labour market tightness in 2024 has been roughly half of what it was in 2022.

This shift suggests that Finland’s labour market is experiencing reduced tightness, potentially due to increased unemployment and fewer available jobs. The alignment with the historical Beveridge curve indicates that these changes are consistent with past labour market dynamics, implying no major change in structural mismatches between job seekers and employers.

Finland is experiencing a more severe economic downturn than the Nordics and the broader euro area, influenced by factors such as trade sanctions related to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and subsequent disruptions in foreign trade. GDP growth projections for 2024 have been significantly downgraded since autumn 2023, highlighting the persistence of the economic downturn. However, positive growth observed in more recent quarters may indicate the beginning of a stabilisation phase. Private investment in particular has contributed negatively to aggregate growth in the last two years but is expected to contribute positively in 2025.

Inflation in Finland has decreased to below , enhancing consumer purchasing power. The most recent data, however, indicates a slight uptick in inflation compared to previous months, mostly attributable to the VAT hike implemented in September 2024 and some correction measures in the data.

Following central bank rate cuts, short-term nominal interest rates in Finland have begun to decline. These lower rates, particularly relevant for most mortgage borrowers, are expected to boost aggregate demand in 2025. In contrast, long-term real interest rates, which are critical for assessing the long-term fiscal cost of public debt, have remained relatively stable following their sharp increase between 2022 and 2023.

Finland has experienced the largest employment rate decline among its Nordic peers since early 2023, although its employment rate remains relatively high compared to historical trends. The Ministry of Finance forecasts a slight decrease in the employment rate in the near term, followed by a modest increase as government measures to boost employment gradually take effect. Analysis of the Beveridge curve indicates reduced labour market tightness, consistent with cyclical dynamics and no significant change in structural mismatches between job seekers and employers.

The wellbeing services counties (WSCs) were established in 2021. Responsibility of providing health and social care and rescue services started as of January 1st 2023, and the WSCs have autonomy in the way in which statutory services are organised and provided. Their financing is mainly based on central government funding. One of the aims of the social and health care reform was to slow down growth in expenditure, and the funding model has some built-in incentives to achieve this. At the same time, the funding must be sufficient to ensure that statutory services are provided to all citizens throughout the country.

The funding of the wellbeing services counties forms a significant proportion, approximately , of the central government budget in 2025. Therefore, an analysis of the WSCs’ finances is crucial from the perspective of the central government budget and public finances as a whole.

Funding for the wellbeing services counties is based on universal imputed central government funding (Act on Funding for the Wellbeing Services Counties 617/2021). Counties have broad autonomy in the use of funding. In addition to central government funding, the counties can collect client and service fees. First, we review the factors that determine the level of funding at the national level.

The level of central government funding in the first year of operation, 2023, was based on the total amount of net expenditure by the municipalities on health and social care and rescue services in 2022, totalling EUR 21.9 billion. Net expenditure means that e.g. client fees and other central government grants are subtracted from the total operating expenditure, so the net expenditure represents the actual amount of expenditure the counties will have to cover by central government funding.

Each year, the level of funding is increased in advance by the wellbeing services counties Price Index (WSC price index, calculated by the MoF). This is a composite index consisting of of the general wage index, of the consumer price index and of the change in employers’ social insurance contributions. The composition of the index is such that the counties cannot directly influence any of its components through their own actions. The WSC price index is set for each year in conjunction with the autumn forecast of the previous year. This is to provide predictability in the level of funding for the following year.

The level of funding is also adjusted annually by the estimated growth in the need for services at the national level (calculated by the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare, THL1 ). This growth estimate is linked to the Statistics Finland population projection, and it projects the annual increase in the need for services. It is updated every four years, with growth estimates for the following four-year period written into the law to provide predictability in the level of funding for the following years. The current estimate of growth in the need for services is approximately in 2023-2027, so funding will increase by approximately EUR 250 million each year.

As the wellbeing services counties have to be able to provide statutory services with central government funding, any legislative changes in their statutory services are taken into account in the level of funding. If statutory tasks are increased or requirements are extended, the funding is increased accordingly, based on the estimated change in costs. This is to ensure that new service obligations are fully funded. If the statutory tasks or requirements are reduced, the funding is reduced by a corresponding amount.

In addition to the revisions made in advance each year, the level of funding is also revised ex post. This ex-post revision of funding is done with a two-year lag and aims to ensure that actual costs at national level do not diverge from the level of central government funding in the longer term.

The ex-post revision of funding is based on the difference between the national level of funding and total net expenditure. If the realised expenditure has exceeded the funding, the shortfall is added to the national level of funding with a two-year lag. The first ex-post revision of funding will take place in 2025, based on the difference between central government funding and the net expenditure realised in 2023. From 2026, the amount of the ex-post revision will take into account the change in the deficit or surplus of the WSCs and the amount of the ex-post revision already added to the funding.

For example, the deficit in 2023 was EUR 1.3 billion, so the first ex-post revision is EUR 1.3 billion, which is added to the funding in 2025.2 The estimated deficit in 2024 is EUR 1.4 billion, i.e. the deficit has increased by EUR 100 million compared to 2023. As the first ex-post revision of EUR 1.3 billion is added to the funding in 2025, the revision in 2026 will add the remaining EUR 100 million. In total, there is a cumulative ex-post revision of EUR 1.4 billion in 2026, which corresponds to the shortfall in funding in 2024.3

The increase (or decrease) in funding is allocated to each county according to the imputed criteria described in more detail below. This means that funding shortfalls in individual counties are not covered on a one-to-one basis. If a county’s share of the total deficit is greater than its share of central government funding, the ex-post revision will only partially cover its deficit. On the other hand, if the county’s share of the deficit is smaller than its share of the funding, the ex-post revision will exceed its deficit. This should provide incentives to keep cost growth under control.

The level of total funding for each budgetary year is determined as described above. The allocation of funding to individual counties is based on imputed criteria, with weights specified in legislation.

To reflect differences in population structure and morbidity, the largest share of the funding, approximately , is allocated on the basis of county-specific service needs for health care, elderly care and social care calculated annually for each county by the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare.

The need for services is first estimated using nationwide individual level data.4 The estimated need for services for each individual is then summed up at the county level to calculate the total need for health and social services in a given county. Finally, the relative coefficients used to allocate funding across counties are calculated by dividing the average need of each county by the national average. A coefficient greater than 1 in health care, elderly care or social care means that the need for services in that sector is higher than the national average, while a coefficient less than 1 means that the need for services in that sector is lower than the national average.

The relative coefficients for each of the three sectors are updated annually for each county based on the latest available data. The imputed funding should therefore be as up to date as possible in capturing changes in the population structure, morbidity and socio-economic factors across the counties.

Approximately of the funding is allocated on a per capita basis. The remaining imputed criteria reflect other county-specific conditions, such as the proportion of bilingual or foreign-language speakers or the population density. The most recent population data is used each year to ensure that the imputed funding reflects changes in the population.

In addition to the imputed funding, there is a county-specific transitional equalisation that is either added to or subtracted from the funding for each county. The purpose is to smooth the transition from the municipal service provision system to WSC-based service provision with full central government funding. The additions and subtractions will decrease over a graded transition period in 2023-2029.

The wellbeing services counties are mainly funded by central government. As the counties do not have the right to levy taxes, the WSCs’ finances are more strictly regulated than those of the municipalities. The wellbeing services counties are obliged to make a financial plan for the following three years that is balanced or in surplus.

If a county runs a deficit, it has to cover it within three years, i.e. a deficit incurred in 2023 and any additional deficit thereafter must be covered by the end of 2026 (Act on Wellbeing Services Counties 611/2021). For example, if a county has a deficit of EUR 10 million in each of the years 2023, 2024 and 2025, it must generate a surplus of EUR 30 million in 2026 to cover the accumulated deficit.

As will be discussed in more detail below, all counties (except Helsinki) were in deficit in 2023. If a county does not manage to generate the required surplus by the end of 2026, it may be subject to an assessment procedure, which means stricter central government control. On the other hand, if it manages to generate the required surplus by the end of 2026, it can in principle run a new deficit in 2027, with a new three-year period to cover it.

The relatively short period for covering deficits is intended to prevent the accumulated deficit in any one county from becoming too large. As counties do not have the right to levy taxes, they must cover the deficit with an equivalent surplus within the limits of central government funding.

Central government funding has to be sufficient for the provision of statutory services while providing some cost control at the same time. The funding model has some built-in incentives to curb growth in social and health care expenditure by keeping the financial framework tight. First, the imputed funding is based on the average cost per service. Given that the funding is also universal, this means that if a county can provide certain services at a lower than average cost, it can use the leftover funding to provide some other services.

Second, the composition of the WSC price index as described above provides some control over cost growth, as it is constructed in such a way that counties cannot directly influence its components.

Third, while the amount of the ex-post revision is based on the funding shortfall at national level, it is allocated to counties in the same proportion as their imputed funding, not in the same proportion as their realised deficits (or surpluses). The first ex-post revision in 2025 fully covers the funding shortfall in WSC finances in 2023. From 2026, the annual increase or decrease in funding through the ex-post revision will be partial (HE 70/2024).

In 2026, the ex-post revision will cover of the increase or decrease in funding. As described in the example above, if the deficit in 2024 is EUR 100 million higher than in 2023, a full ex-post revision would add EUR 100 million to the national level of funding in 2026. With a revision the increase will be EUR 95 million. The partial ex-post revision will thus reduce funding by EUR 5 million compared to a full revision in 2026. On the other hand, if the deficit in 2024 were EUR 100 million lower than in 2023, the full ex-post revision would reduce funding by EUR 100 million. The revision would reduce funding by EUR 95 million, i.e. the funding would be EUR 5 million higher than with a full revision. The increase or decrease will gradually decrease to of the revision in 2029.

In addition to the incentives built into the central government funding model, the obligation to cover deficits within a three-year period combined with the threat of being subject to stricter central government control is expected to act as a further incentive to curb cost growth.

The first year of operation was financially difficult for the wellbeing services counties. The deficit in the WSCs’ finances was EUR 1.3 billion in 2023, and is projected to be even higher in 2024. In this section we first discuss the reasons for these high deficits at national level, and then assess the required consolidation to achieve balanced WSC finances by the end of 2026.

Expenditure growth in the wellbeing services counties has been very rapid. Net expenditure on health, social and rescue services amounted to EUR 24.5 billion in 2023. It increased by EUR 2.6 billion compared to what the municipalities spent on these services in 2022, representing nominal growth of . The main reasons for the high expenditure growth in 2023 are the wage agreement in the health and social care sector, high inflation, and increased reliance on expensive agency doctors.

Approximately of total operating expenditure in 2023 was spent on personnel costs, most of which were wages and salaries for own staff. In the summer of 2022, a new wage agreement was negotiated in the municipal sector for the years 2022-2025, linking wage increases in the municipal sector to wage increases in export industry. In October 2022, a further wage agreement was reached in the social and health care sector, including integration and development of pay systems. According to the Ministry of Finance (2024a), wages and salaries in the WSCs increased by in 2023. The wage agreement also has an impact on costs in 2024 and 2025, and the Ministry of Finance projects wages and salaries in the WSCs to increase by in 2024 and in 2025.

In 2023, of operating expenses were spent on the purchase of services. This was almost , or EUR 1.2 billion more than the WSCs had budgeted for 2023. The use of agency doctors and nurses increased due to labour shortages in many counties. Also, contracts with private service providers, especially in elderly care, were renewed in 2023 with high price increases. In addition to the increase in personnel costs, inflation also remained high in 2023, with the consumer price index rising by .

The previous government also implemented stricter requirements for 2023 in the midst of labour shortages that may have increased cost pressure in the counties. The minimum staffing requirement for elderly care was increased from the beginning of April 2023, and the maximum waiting times for access to care were shortened. It is possible that these stricter requirements forced the counties to increase salaries to attract qualified staff or to increase the use of agency doctors and nurses to meet the requirements.5

The above reasons explain the cost increases in 2023. The high level of expenditure in 2023 may also reflect inaccuracies in final net expenditure in 2022. In the reform, total net expenditure on social and health care and rescue services in 2022 defined the cuts in municipalities’ funding. The higher the total expenditure, the higher the cuts in central government transfers to municipalities. The municipalities therefore had an incentive to underbudget social and health care costs in order to minimise the cuts to their own funding.

Some of the underbudgeting was corrected afterwards using the final expenditure data for 2022. According to the municipalities’ draft budgets for 2022, total expenditure for social and health care and rescue services was EUR 21.2 billion. This was revised upwards by around EUR 650 million on the basis of the municipalities’ financial statements and some specific accounting entries that distorted the actual amount of spending on these services (Decree 886/2023). However, despite these revisions, it is still possible that the municipalities minimised the impact of the reform on their own finances by limiting their spending on health care and social services in the pre-reform years.

The COVID-19 pandemic distorted service provision in the pre-reform years by causing treatment queues as many treatments were postponed. These queues were at least partially resolved in 2022, but it is difficult to say to what extent 2022 was a normal year for the provision of health and social care services. The pandemic also distorted the financing of health services, as central government compensated the municipalities for the extra costs associated with it. If the government grants exceeded the pandemic-related costs, the net expenditure may have been too low for some municipalities. As the total amount of net expenditure was used as the basis for central government funding to the WSCs, excessive pandemic-related grants mean that there might be a permanent shortfall in the national level of funding.6

Finally, there are always start-up costs associated with reforms of this scale. The transfer of service provision from the municipalities to the wellbeing services counties required, for example, integration of the service, ICT and wage systems. Central government has funded these start-up costs through separate grants, but it is likely that the costs have exceeded these grants.

In August 2024, the wellbeing services counties reported their projections for 2024. According to these, expenditure growth in 2024 was estimated to be . Wages in the social and health care sector were still growing more than the general wage index, but inflation slowed down. As growth in expenditure slowed from 2023, it may indicate that the counties have begun implementing various savings and productivity-increasing measures. The Ministry of Finance forecasts that expenditure growth will remain around in the coming years too.7

While expenditure has grown rapidly, central government funding has not grown at the same rate. As described in section 3.1, the level of central government funding in 2023 was defined by the total net expenditure (EUR 21.9 billion) of municipalities on health and social care and rescue services in 2022. The EUR 650 million revision discussed above has been corrected both in the central government funding for 2023 in a one-off payment in January 2024 and in the level of central government funding from 2024 onwards. The funding base should thus reflect the actual final expenditure of the municipalities in 2022.

The funding for 2023 was increased by the WSC price index () and by the estimated growth in the need for services (). The changes in statutory tasks brought in by the previous government were also taken into account with a corresponding increase in funding.

In total, central government funding for 2023 was EUR 23.2 billion, which was , or EUR 1.3 billion higher than what the municipalities spent in 2022. Against the increase in expenditure, the deficit in 2023 was EUR 1.3 billion. In 2024, funding grew by compared to 2023, while expenditure growth is estimated at , resulting in a projected deficit of EUR 1.4 billion in 2024.

Funding has grown much less than expenditure primarily due to the way the WSC price index is constructed and applied. The index reflects changes in the general wage level with a weight, with wage increases in the social and health care sector that exceed increases in the general wage level being only partially captured.

For 2023, the WSC price index used to determine funding levels was based on the Ministry of Finance’s autumn 2022 forecast (Ministry of Finance, 2022), which preceded the final wage agreement for the social and health care sector. At that time, the general wage index was estimated to increase by . After incorporating the actual wage agreement, the increase in the general wage level for 2023 was later revised to (Ministry of Finance, 2024a).

Additionally, of the WSC price index is based on the consumer price index (CPI) forecast. The funding level for 2023 was determined using the autumn 2022 forecast of inflation, whereas the realised inflation rate was significantly higher at (Ministry of Finance, 2024a).

In other words, the funding was based on wage and consumer price inflation forecasts that both turned out to be lower than the actual realisations. Consequently, the WSC price index for 2023 was underestimated relative to the actual increase in costs. Ex-post, a rough estimate of the “correct” WSC price index increase for 2023 would be ,8 whereas funding was based on an increase of just .9

This implies that the WSC price index used to adjust funding for 2023 was approximately 1.3 percentage points too low, implying a shortfall of around EUR 300 million. The resulting cumulative impact of around EUR 600 million for 2023 and 2024 is quite substantial. While the first ex-post revision of funding will correct the level of funding from 2025 onwards, it will not correct the funding for 2023 and 2024 ex-post.

As described above, the total deficit of the WSCs’ finances in 2023 is EUR 1.3 billion and the estimated deficit in 2024 is EUR 1.4 billion. To cover the accumulated deficit, the WSCs will have to generate a total surplus of EUR 2.7 billion by the end of 2026, within the limits of central government funding. Next, we will discuss the magnitude of the required consolidation to generate this surplus.

The first ex-post revision of funding is based on the total deficit in 2023. Adjusted to the price level of 2025, an ex-post revision of EUR 1.4 billion is added to the funding in 2025. In total, the funding increases by EUR 2.2 billion, or compared to 2024. In 2026, an ex-post revision of EUR 160 million is added to the funding, bringing the total ex-post revision to almost EUR 1.6 billion in 2026.

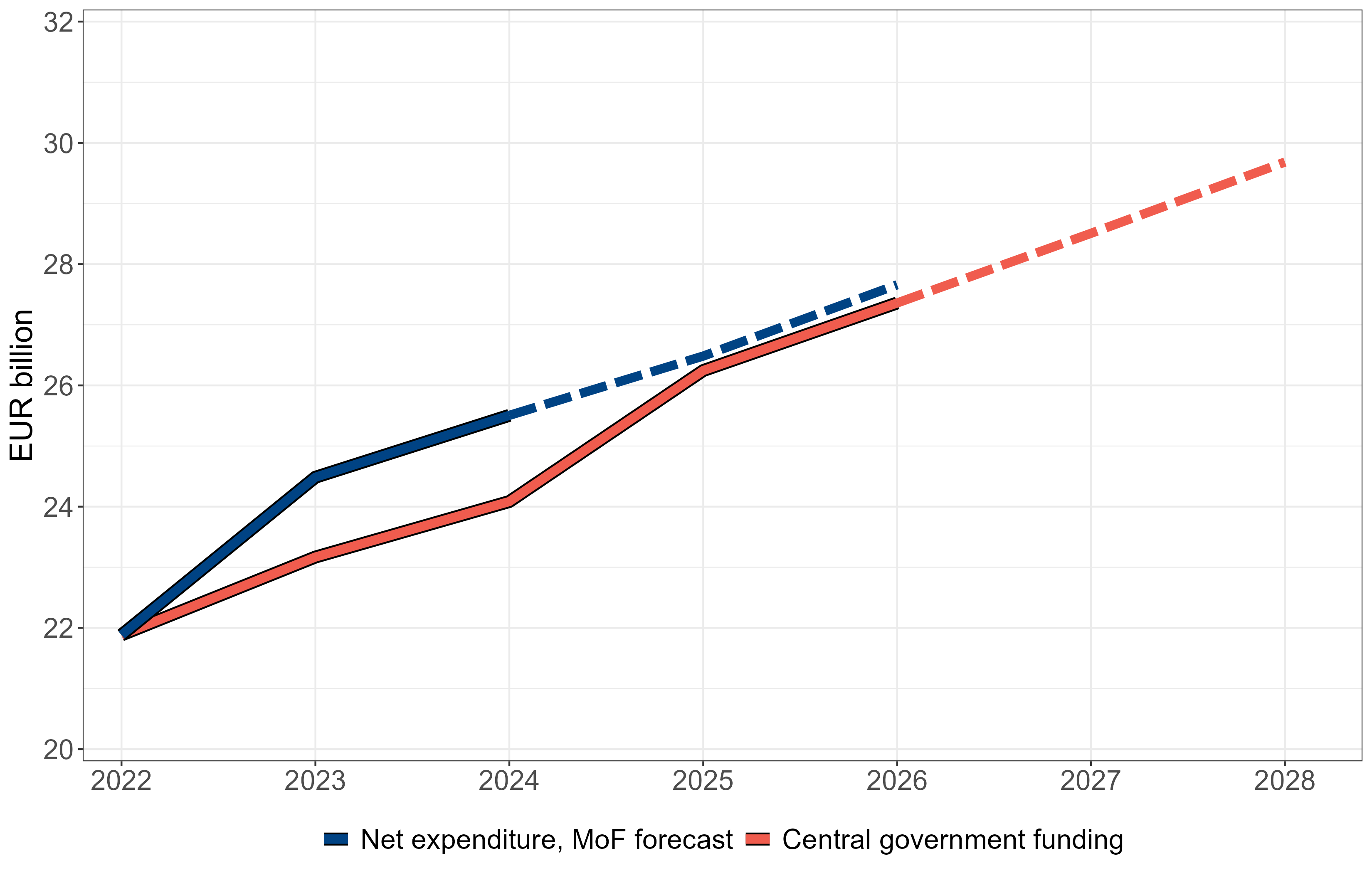

Sources: State Treasury, Ministry of Finance, and Council’s calculations. Notes: WSC expenditure in 2023 is based on realised data and in 2024 is based on an estimate. WSC expenditure in 2025 and 2026 (blue dashed line) is based on MoF autumn 2024 forecast. Central government funding in 2025 and 2026 accounts for deficits in 2023 and 2024. Central government funding in 2027 and 2028 (red dashed line) is calculated based on projected deficits in 2025 and 2026 given the path for expenditure in the figure.

Figure 3.2.1 shows realised expenditure in 2023 and estimated expenditure in 2024 (blue solid line). Expenditure in 2025 and 2026 is based on the Ministry of Finance’s autumn 2024 forecast10 , according to which net expenditure grows by approximately per year (blue dashed line). The figure shows the significant increase in funding in 2025 and 2026 (red solid line) based on the deficits in 2023 and 2024. The ex-post revision, and thus the total level of funding for the years 2027 and 2028 (red dashed line), is based on the projected deficits in 2025 and 2026.

Figure 3.2.1 shows that the substantial increase in funding will help to balance the WSCs’ finances as a whole, as with the ex-post revision the level of the central government funding converges to the level of expenditure. However, it is not sufficient to generate the required surplus if expenditure grows at the projected rate of per year in 2025 and 2026. The cumulative deficit would be close to EUR 3 billion at the end of 2026.

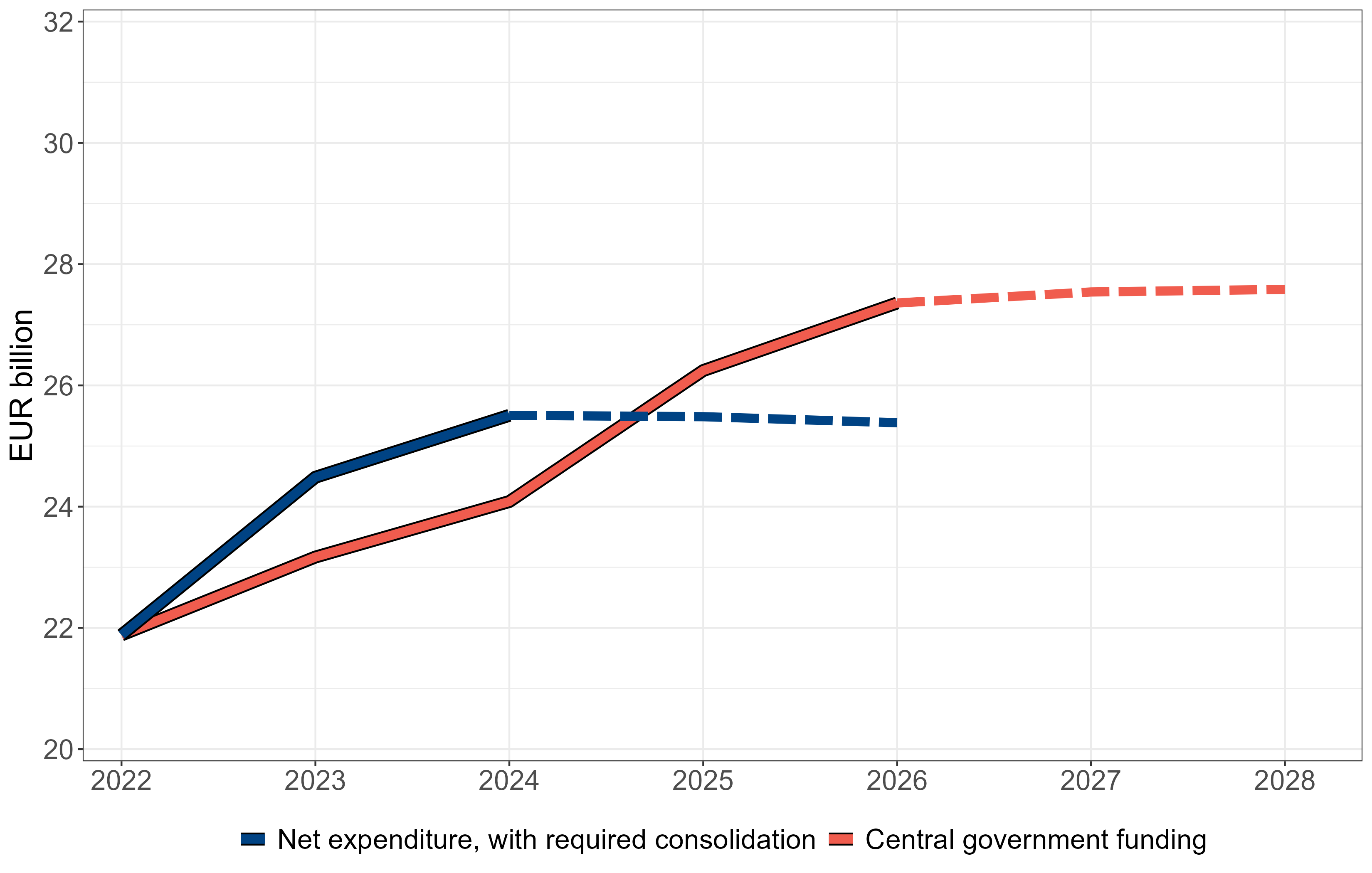

Instead, for the WSCs to be able to cover the accumulated deficit, growth in expenditure must be significantly lower in 2025 and 2026 than in the MoF projection. Given the same increase in funding in 2025 and 2026 (red solid line) as in Figure 3.2.1, Figure 3.2.2 shows an example of the maximum expenditure growth in 2025 and 2026 (blue dashed line) that would generate the required surplus by the end of 2026.

Sources: State Treasury, Ministry of Finance, and Council’s calculations. Notes: WSC expenditure in 2023 is based on realised data and in 2024 is based on an estimate. WSC expenditure in 2025 and 2026 (blue dashed line) is a scenario, in which the WSCs cut expenditure sufficiently to cover the accumulated deficits (see text for details). Central government funding in 2025 and 2026 accounts for deficits in 2023 and 2024. Central government funding in 2027 and 2028 (red dashed line) is calculated based on projected deficits/surpluses in 2025 and 2026 given the path for expenditure in the figure.

According to our calculations, at the national level, net expenditure in nominal terms should be approximately lower in 2026 than in 2024 to ensure a sufficient surplus in the WSCs’ finances by the end of 2026. This means that the level of expenditure would be approximately EUR 2 billion lower in 2026 than in the MoF forecast. The exact size of the required consolidation depends on the timing of the measures in 2025 and 2026.

Figure 3.2.2 shows that if the counties manage to cut their spending sufficiently to generate the required surplus, the level of funding is significantly higher than the level of expenditure at the end of 2026. Furthermore, while the ex-post revision reduces funding in 2027 and 2028 in response to spending cuts in 2025 and 2026, the level of funding in 2028 will not fully converge downward to the level of spending in 2026, as can be seen in Figure 3.2.2. This is because the annual ex-ante adjustments based on the WSC price index and the growth in the need for services partially offset the downward ex-post revisions. This means that while the level of funding is higher than expenditure at the end of 2026, it also remains higher in 2027 and 2028 (red dashed line).

As described in section 3.1, if the counties manage to generate the required surplus by the end of 2026 to cover the deficits incurred in 2023 and 2024, they can in principle start running a new deficit in 2027 with a new three-year period to cover it.

In the example shown in Figure 3.2.2, the level of central government funding is EUR 2 billion higher than expenditure in 2026. At the national level, this means spending could be increased by for the WSCs’ finances to be balanced, or even more to run a small deficit in 2027. This rapid increase in costs in 2027 would in turn mean an increase in funding with the two-year lag in 2029 due to the ex-post revision.

The WSCs’ finances are therefore potentially volatile. This volatility is caused by the large deficits in 2023 and 2024 that were at least partly caused by underfunding. The obligation to cover the deficits within a strict timeframe will force the counties to cut spending significantly in 2025 and 2026. As funding does not fully converge downwards to the level of expenditure, the counties can increase spending significantly in 2027.

If funding had been cumulatively the estimated EUR 600 million higher in 2023 and 2024 (other things constant), this would mean less pressure to consolidate in 2025 and 2026, and would potentially reduce the fluctuation in the level of funding in later years.

The partial ex-post revision described in section 3.1 can to some extent reduce the volatility in the longer term, as the ex-post revisions will cover only of the additions or reductions from 2029. Both the additions and reductions will be smaller than with the current model of ex-post revision. This means that the counties’ ability to increase spending is smaller, but also their need to cut spending in subsequent years is likely to be smaller. However, as the partial ex-post revision changes the amount of funding already from 2026, exact analysis of the partial ex-post revision would require assumptions about the counties’ responses to changes in funding.

Above, the WSCs’ finances have been analysed as a whole. It is important also to analyse the individual counties, as there is a great deal of heterogeneity between counties in terms of population structure, geography, integration of the service structure and finances. Next, we discuss the financial outlook at the county level.

As discussed above, expenditure at the national level increased by in 2023 compared to what the municipalities spent on equivalent services in 2022. There were large differences in expenditure growth between the WSCs: expenditure grew by in Helsinki, while it grew by in Vantaa-Kerava, Itä-Uusimaa and Lappi.

According to the WSCs’ 2024 projections, expenditure growth slowed down in almost all of the counties in 2024. At the national level, expenditure growth is estimated to be approximately in 2024, but there are several counties where expenditure growth was projected to be slower. Figure 3.3.1 shows the growth in expenditure in 2023 (blue bars) and in 2024 (yellow bars) compared to the level of expenditure in 2022 in all wellbeing services counties.

Sources: State Treasury and Ministry of Finance.

It can be seen that the expenditure in Vantaa-Kerava in 2024 is more than higher than what Vantaa and Kerava spent as municipalities in 2022. At the same time, expenditure has increased by in Helsinki.

The reasons for the rapid expenditure growth at the national level, in particular the impact of the wage agreement and high inflation, apply more or less to all counties. At the beginning of 2023, there were large differences in the degree of service and ICT systems integration and in wage harmonisation between the counties. These caused a varying amount of start-up costs, and explain at least part of the variation in expenditure growth. Also, the costs in the reference year 2022 may have been incorrectly understated for some counties, resulting in high expenditure growth in 2023.

However, regardless of the reasons for the high cost growth, counties face the same obligation to balance their finances by the end of 2026.

Central government funding of EUR 23.2 billion for 2023 amounted to EUR 4200 per capita. The largest share of the funding, EUR 2.6 billion, was allocated to Helsinki, and the smallest share, EUR 0.3 billion, was allocated to Keski-Pohjanmaa.

The allocation of funding across counties is based on the imputed criteria from the first year 2023. The imputed funding is intended to reflect the cost of providing statutory services due to differences especially in population structure, morbidity and socio-economic factors, but also in the languages spoken in the county and the population density. Due to this allocation mechanism, there is a large variation in per capita funding between the counties.

Figure 3.3.2 shows per capita funding in each county in 2023 divided into different criteria. Imputed per capita funding is highest in the counties of Northern and Eastern Finland, and lowest in the counties of Southern Finland. The highest per capita funding in 2023 was in Lappi, EUR 5300, and the lowest in Länsi-Uusimaa, EUR 3500.

Source: Ministry of Finance.

However, the difference between the imputed funding and the municipalities’ expenditure on social, and health and rescue services is somewhat significant for some of the counties. Therefore, in order to smooth the transition from the municipal system to full central government funding, there is a separate addition to or subtraction from the imputed funding for each county based on a county-specific transitional equalisation (not shown in Figure 3.3.2).

The equalisations are calculated as the difference between the imputed funding in each county in 2022 and the total net expenditure by the municipalities in each county in 2022. This difference is added to or subtracted from the imputed funding fully in 2023. The amount of the additions or subtractions are decreasing in a graded transition period until 2029, and they are not subject to the annual cost level revisions described in section 3.1. As the level of the imputed funding is adjusted annually to reflect changes in costs, the significance of the equalisations decreases over time.

In 2025, for 13 counties the additions or subtractions through the transitional equalisations are less than of their imputed funding. The largest subtraction in 2025 is for Pohjois-Karjala, with , or EUR 61 million (EUR 380 per capita) reduction to its funding. The largest addition is for Etelä-Savo, with , or EUR 37 million (EUR 280 per capita) addition. For Helsinki, too, the transitional equalisation is quite substantial, with or EUR 135 million (EUR 200 per capita) addition to its funding in 2025.

Above, Figure 3.3.2 shows how the funding is allocated across the counties in 2023. When assessing the economic outlook at county level, the increase in funding in each county is also of importance. As described in section 3.1, the national level of central government funding is adjusted annually according to the WSC price index and other revisions. These revisions are intended to ensure that funding is sufficient for the provision of services at the national level, while providing some cost control.

However, this adjustment in national funding is unevenly distributed. This is because the allocation of funding across counties is updated annually based on the latest population data and the revised county-specific coefficients for healthcare, elderly care and social care. The annual increase in funding for each county therefore reflects not only the cost level revisions, but also changes in their population, morbidity and socio-economic factors.

Figure 3.3.3 shows the uneven growth in funding in 2025 relative to 2024 in each county (black dots), which is largely due to the revision of allocation across the counties. In the figure, the growth is divided into three factors: i) the increase due to revisions by the WSC price index and growth in the need for services, and the impact of the revised allocation of funding between the counties (including the graded equalisations) (blue bars), ii) the change in funding due to changes in statutory tasks (green bars), and iii) the the ex-post revision (yellow bars).

Source: Ministry of Finance and Council’s calculations.

Taking into account all the annual revisions, the average increase in funding in 2025 is , ranging from in Etelä-Karjala to in Vantaa-Kerava. The blue bars in Figure 3.3.3 show the main reason for this variation. There is an average increase of in 2025 due to the ex-ante adjustments due to the WSC price index and the estimated growth in the need for services. This increase is allocated to each county based on the revised allocation of funding in 2025. As a result of this, funding grows by in Vantaa-Kerava, but only by in Etelä-Karjala.

According to the central government budget proposal for 2025, there is a reduction of EUR 270 million due to changes in the statutory tasks and requirements, meaning a reduction in funding on average. The first ex-post revision in 2025 increases funding by an average of .

For many of the counties in the bottom half of Figure 3.3.3, the increase in funding in 2025 is largely due to the ex-post revision, as the increase due to the WSC price index and growth in the need for services is largely offset by the reallocation of funding and reductions due to legislative changes.

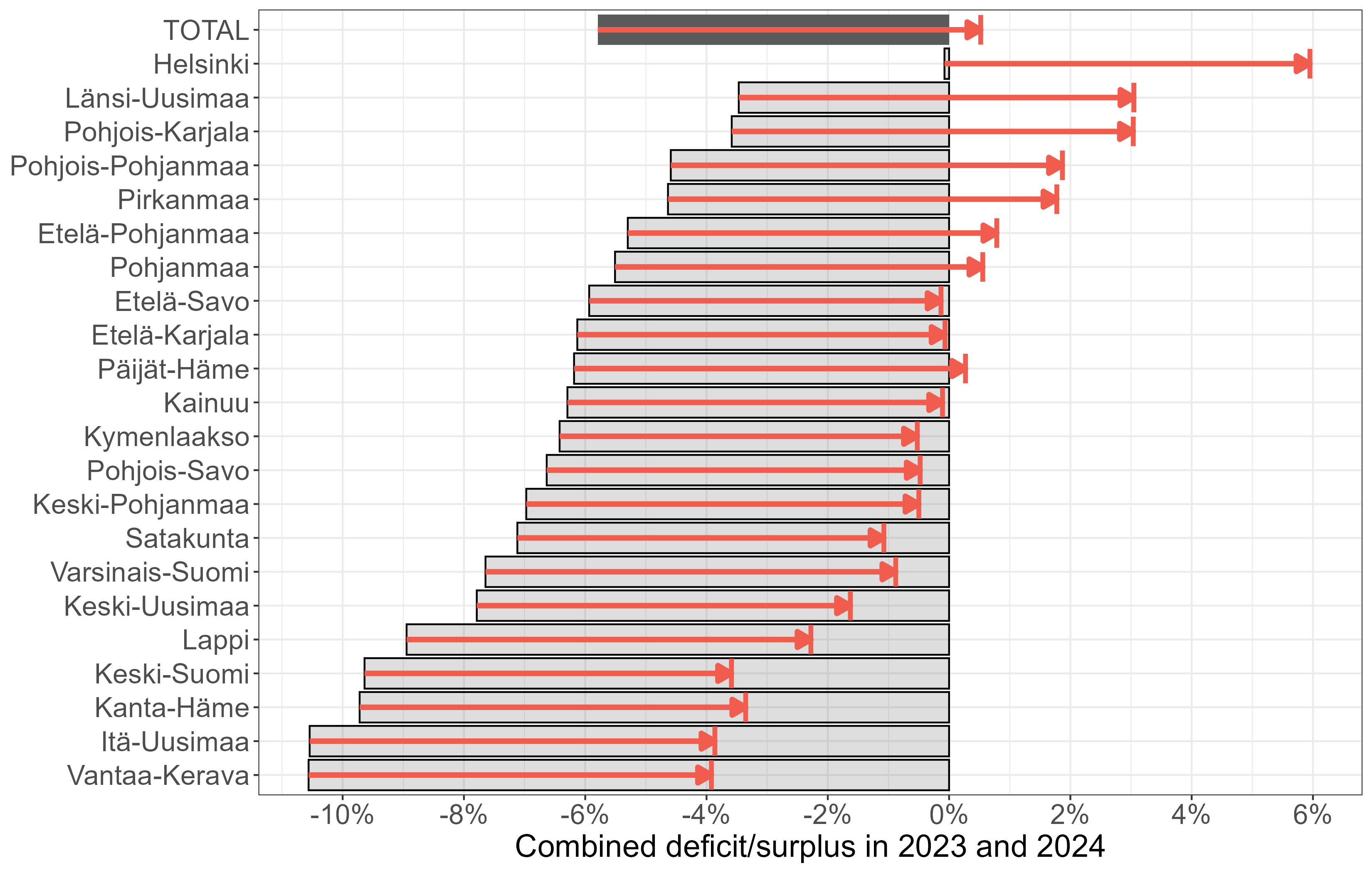

As a result of the high expenditure growth, all counties except for Helsinki were in deficit in 2023. All counties including Helsinki are also projected to be in deficit in 2024. Grey bars in Figure 3.3.4 show the cumulative deficits in 2023 and 2024 in each county relative to the amount of their central government funding in 2023 and 2024. The cumulative deficit at the national level is of the total amount of funding in 2023 and 2024. The largest accumulated deficits, , are in Vantaa-Kerava and Itä-Uusimaa, while Helsinki is close to having a balanced economy in 2023-2024.

Sources: State Treasury, Ministry of Finance, and Council’s calculations. Notes: The red arrows indicate the amount of the cumulative deficit in 2023-2024 covered by the ex-post revision in 2025-2026.

At national level, the total amount of the ex-post revision in 2025 and 2026 corresponds to the deficits in 2023 and 2024, adjusted for cost revisions. It is allocated to individual counties in the same proportion as their imputed funding. The share of the ex-post revision in 2025 and 2026 allocated to each county is illustrated by the red arrows in Figure 3.3.4.11

The red arrows in the figure show how much of the cumulative deficit in 2023 and 2024 will be covered by the ex-post revision in 2025 and 2026 in each county. Due to the cost level adjustment, the ex-post revision slightly over-compensates the cumulative deficit at the national level.

As can be seen in Figure 3.3.4, there are eight counties for which the ex-post revision in 2025 and 2026 exceeds their cumulative deficits in 2023 and 2024. These counties will have their deficits covered or are even over-compensated by the ex-post revision. Even Helsinki that is close to having a balanced economy in 2023-2024, will have an ex-post revision of an estimated EUR 320 million in 2025-2026.

On the other hand, there are 14 counties with an accumulated deficit in 2023-2024 larger than their share of the ex-post revision in 2025-2026. In total, the accumulated deficit to be covered after accounting for the ex-post revision is approximately EUR 400 million.

It is important to recall that while the ex-post revision covers the accumulated deficits at the national level, it is not sufficient to generate the required surplus, as discussed above in relation to Figures 3.2.1 and 3.2.2. Significant spending cuts are also required. According to the example presented in Figure 3.2.2, the level of expenditure at the national level in 2026 should be approximately lower (in nominal terms) than in 2024 after taking into account the increase in funding due to the ex-post revision for there to be a sufficient surplus.

Compliance with the requirement to cover the accumulated deficits by the end of 2026 is assessed for each county, not for the WSCs as a whole. Therefore, it is important also to assess the variation in the required consolidation across counties. Many counties will have to cut their spending substantially more than in the example above to generate the required surplus. The amount of the required consolidation depends on how much of the cumulative deficit is uncovered after taking into account the ex-post revision, but also on how their central government funding grows in 2025 and 2026.

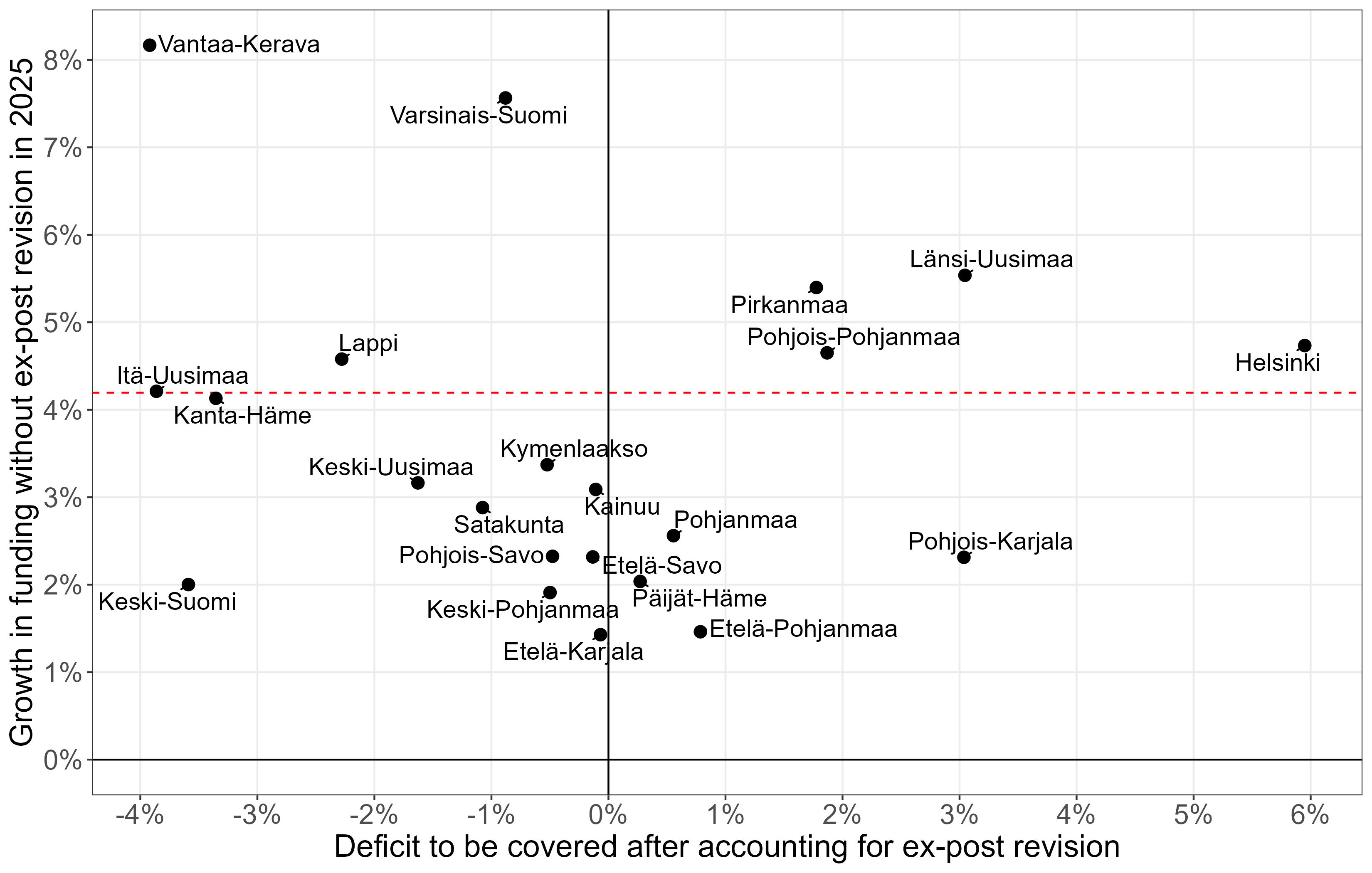

In Figure 3.3.5, the cumulative deficit in 2023-2024 after accounting for the ex-post revision in 2025-2026 in each county relative to their total funding in 2023-2024 is plotted on the horizontal axis. This represents the amount of the cumulative deficit that is remaining after taking into account the ex-post revision. The increase in funding in 2025 without the ex-post revision12 is plotted on the vertical axis. The red dashed line represents the average growth () in funding in 2025.

Sources: State Treasury, Ministry of Finance and Council’s calculations. Notes: Deficit on the horizontal axis is relative to cumulative funding in 2023-2024. Red dashed line represents average growth in funding.

The counties to the left of the mark on the horizontal axis in Figure 3.3.5 are those where the ex-post revision will not cover their accumulated deficits. The tightest financial framework is for the counties in the bottom left of the figure, as their funding grows less than the national average in 2025. These counties would need to make the largest cuts in spending in 2025 and 2026 in order to generate sufficient surplus to cover their deficits. The ex-post revision will not cover the deficits in counties in the top left of the figure, but their funding grows more than national average.

Of the counties on the left-hand side part of the figure, Vantaa-Kerava and Keski-Suomi are approximately the same size in terms of their budgets (EUR 1.2 billion) and the amount of the deficit to be covered after taking into account the ex-post revision (EUR 80 million). Funding without the ex-post revision grows by in Vantaa-Kerava, but only by in Keski-Suomi. In order to generate the required surplus, Keski-Suomi will have to reduce its expenditure substantially more than Vantaa-Kerava.

The ex-post revision over-compensates the accumulated deficits for counties to the right of the mark on the horizontal axis. Counties in the top right of the figure have their accumulated deficits covered by the ex-post revision, and their funding also increases more than the average. These counties face less or no consolidation pressure at all. It is worth noting these counties are the biggest ones in terms of their budgets and population. Of these, Helsinki is on its own level, meaning that it does not have the same consolidation timeline as the rest of the counties.

Here, we have discussed how the scale of the required consolidation varies across counties, depending on the amount of the accrued deficits and the funding outlook. At this stage, it is not possible to calculate the exact amount of consolidation required for each county, as the analysis has been based on the figures projected in August 2024, and funding for 2026 is based on a rough estimate by the Ministry of Finance. Once the final figures for the financial year 2024 are reported in spring 2025, and the funding for each county in 2026 is calculated by the Ministry of Finance, a more accurate assessment of the required spending cuts in each county can be made.

The built-in incentives in the funding model are working for most counties, as their financial frameworks are tight, forcing them to cut their costs. In practice, their ability to cut spending depends largely on whether rapid growth in expenditure has been due to one-off costs, or whether the costs are more permanent in nature. If the high costs can be largely explained by one-off start-up costs, it is more likely that these counties can cut their spending in 2025 and 2026. If the high costs are related more to permanent cost increases, then cost-cutting needs more drastic measures.

As mentioned above, there is approximately EUR 400 million of cumulative deficit in 2023 and 2024 that is not covered by the ex-post revision in 2025 and 2026. This further adds to the already significant consolidation pressure to generate sufficient surplus by the end of 2026, which requires that expenditure growth should be kept close to (or even slightly below) zero in nominal terms in 2025 and 2026. It is likely that not all counties manage to implement the required savings by the end of 2026, but need to continue their consolidation in 2027 too.

The ex-post revision is a statutory part of central government funding, and the government has set the central government spending limits based on a certain level of expenditure by the WSCs. The rapid expenditure growth in the WSCs therefore poses a challenge for the central government budget and for the sustainability of public finances as a whole.

The counties’ own consolidation measures are reflected in a lower level of central government funding through the ex-post revision with the two-year lag. If the WSCs succeed in reducing expenditure in 2025 and 2026, as shown in Figure 3.2.2, the level of funding in 2028 will be lower than in Figure 3.2.1, which shows projected expenditure growth without the counties’ own consolidation measures.

As the projected deficits in the WSCs in 2023 and 2024 have increased during this government term, the amount of funding for the WSCs has been adjusted in the central government spending limits decisions, first in autumn 2023 and again in spring 2024.

In the spring of 2024, the government reserved funding for the ex-post revision for the years 2025-2028 based on an estimate of realised expenditure in 2023 and on the projected expenditure in 2024–2026 that the counties had reported in their financial plans. According to the counties’ financial plans, the WSC finances would run a deficit of EUR 900 million in 2024, and would then turn into a surplus in 2025. The funding reserved on the basis of this projection (at 2025 prices) is EUR 1460 million in 2025, EUR 959 million in 2026, EUR 392 million in 2027 and EUR -131 million in 2028.

As counties have a legal obligation to prepare a financial plan that is balanced or in surplus, the financial plans were optimistic or even unrealistic for many counties. In order to be prepared for a higher trajectory of expenditure and thus to be able to cover a higher level of funding, the government decided in spring 2024 on an earmarked provision for the ex-post revision. The spending limits provision is EUR 35 million in 2025, EUR 437 million in 2026, EUR 924 million in 2027 and EUR 627 million in 2028. This earmarked provision cannot be used to finance any other spending than the ex-post revision.

Whether the funding reserved for the ex-post revision (including the earmarked provision) will be sufficient, especially in the last two years of the government’s term, 2026 and 2027, will depend on how the counties manage to curb expenditure growth in 2024 and 2025. As discussed above, the deficit in 2024 is approximately EUR 1.4 billion euros according to the counties’ own projections (as of August 2024). This is EUR 550 million higher than the estimated deficit in their budget plans for 2024. This means that the funding allocated to the ex-post revision for 2026 will not be sufficient, and also that the spending limits provision for 2026 will be exceeded by approximately EUR 150 million.

To cover this shortfall, the government will have to use the unallocated reserve within the spending limits or find either direct savings from the WSCs or elsewhere in the central government budget within the spending limits. If the actual deficit in 2024 surpasses the estimate made in autumn 2024, the spending limits will be breached more, and the government will have to find even more compensating savings elsewhere.

The sufficiency of the ex-post funding reserved for 2027 will depend on the final outcome of the financial year 2025. According to our calculations, expenditure growth at the national level would need to slow to around in 2025 for the funding reserved in the spending limits (including the earmarked provision) to be sufficient in 2027. This corresponds to a total consolidation of EUR 500 million in 2025 compared to the projected expenditure growth in the MoF autumn 2024 forecast.

As discussed above, the obligation to cover the accumulated deficit by the end of 2026 would require expenditure growth at the national level to slow to closer to zero or even be negative. Thus the obligation to cover the accumulated deficit imposes a stricter adjustment requirement than the sufficiency of the spending limits.

The government has proposed several measures to slow growth in expenditure in the wellbeing services counties. According to Annex B of the government programme, a total of EUR 1.3 billion of the consolidation in public finances is allocated to the social and health care sector by the end of the government term in 2027. In spring 2024, the government decided on a package of additional measures worth EUR 470 million by 2027.

The measures can be categorised into three ways in which they are expected to strengthen the public finances: i) wellbeing services counties’ own savings and productivity-increasing measures, ii) legislative changes in social and health care services with corresponding cuts in central government funding, and iii) cuts in central government funding without legislative changes in social and health care services. Each of these ways is discussed in more detail in the following.

First, approximately EUR 900 million of the planned consolidation is based on savings and productivity-increasing measures by the counties. In practice, this means that the counties would curb the growth in expenditure by means of their own measures. If the counties manage to curb the expenditure growth as projected in the government programme, the WSCs’ finances are expected to strengthen gradually in 2025-2027.

At this point, it is unclear what the exact impact of the counties’ own measures on the public finances will be. On the other hand, the counties have implemented productivity-enhancing measures and direct savings, but the wage agreement in the health and social care sector is still affecting their costs. Therefore, assessing these productivity increasing measures is not so straightforward.

Second, the government has decided on a set of legislative changes that reduce the range of statutory service provision and relax some of the personnel requirements. As described in section 3.1, reductions in the statutory tasks and obligations are cut from funding according to the estimated reduction in costs at the national level. Funding cuts are allocated to each county based on imputed funding - not one-to-one with actual cost reductions in each county.

The cuts to funding announced in the government programme amount to a total of EUR 440 million in 2027. A set of additional cuts of EUR 470 million by 2027 were decided in spring 2024. Some of the cuts are discussed below.

The government has decided to lower some of the personnel requirements decided by the previous government. These changes should help the counties to curb the growth in expenditure, but also help them to deal with the shortage of qualified staff in the health and social care sector.

In the government programme, it was decided that the requirement for minimum staffing in elderly care was to be maintained at the level in force when the current government took office, and the previous government’s decision to increase the requirement was postponed until 2028. The requirements regarding qualified staff in elderly care were also relaxed to help recruitment. In spring 2024, to achieve additional savings, the government decided to first lower the minimum staffing requirement in elderly care from 2025, and to cancel the planned increase altogether.

The government has also made decisions regarding the maximum waiting times for access to primary health care. In the government programme it was decided to maintain the maximum waiting time at 14 days, and the decision by the previous government to shorten it to seven days was cancelled. In spring 2024, the government decided to increase the maximum waiting time to 3 months in primary health care and from 4 months to 6 months in oral health care.

The savings associated with these changes, first to cancel the plan to shorten the maximum waiting time to 7 days, and then to further extend it to 3 months, are largely based on reversing the funding increases of the previous government. The previous government’s decision to shorten the maximum waiting time was estimated to lead to a permanent cost increase in primary and oral health care, for example through the need to recruit more staff. Based on the estimated cost increase, central government funding was increased correspondingly.

According to the government proposal (134/2024), estimating the actual savings of these changes is difficult. Some of the changes by the previous government were already implemented in 2023 with corresponding increases in funding. Since the central government funding is universal, it is difficult to detect how much of the funding was used to cater for the stricter requirement, especially with the WSCs running significant deficits in 2023. Also, it is not clear how extending the waiting times to care will help make savings, especially in the longer term. It is possible that this change will increase the use of emergency services, and therefore end up increasing costs instead of reducing them. Also, this change is in contrast with the reform’s aim of facilitating access to primary health care.

The government also decided to increase the client fees the counties can collect. The maximum client fees in primary health care will be and in specialised health care higher in 2025 (Decree 543/2024). To ensure this is a cost-saving measure for central government, the funding model is changed so that legislative changes in client fees will be taken into account in the level of central government funding in advance (HE 70/2024).

The government has also proposed several changes to the range of social and health care services the wellbeing services counties are required to provide, with corresponding cuts in funding.

The third way to curb cost growth is through direct cuts in central government funding without corresponding changes in statutory tasks. According to the government programme, there will be a direct cut of EUR 65 million in funding in 2027. This proposed cut is relatively moderate. The direct cuts in funding without corresponding changes in statutory tasks will strengthen the public finances only if the counties can adjust their provision of services to the lower level of funding.

The rapid growth in spending by the wellbeing services counties significantly hampers the government’s goal of stabilising the public debt-to-GDP ratio by the end of the parliamentary term and may make it difficult to adhere to the previously agreed spending limits in central government finances.